So why is our modern world dominated by images of the body that are unrealistic?

Neuroscientists theorize this has something to do with the workings of the human brain, and point to a neurological principle known as the peak shift. In essence our brain is hard-wired to focus upon parts of objects with pleasing associations. So if you were an artist, the tendency would be to reproduce human figures with parts that mattered the most to you.

Our brain is hard-wired to focus upon parts of objects with pleasing associations.

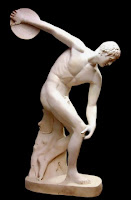

Prehistoric artists were clearly caught up in peak shift tendencies, creating exaggerated statues like the famed Venus of Willendorf. For their part, the Egyptians perfected a more stylized, order-obsessed human figure, only to have the Greeks break out and create fantastically heroic — but totally unrealistic — images like the Riace Bronzes.

So why then are we moderns constantly inundated by unrealistic images of the body?

In reality, we humans don't really like reality - we prefer exaggerated, more human than human, images of the body. This is a shared biological instinct that appears to link us inexorably with our ancient ancestors.

The Venus Of Willendorf

The Venus of Willendorf is one of the earliest images of the body made by humankind. It stands just over 4 ½ inches high and was carved some 25,000 years ago. It was discovered on the banks of the Danube River, in Austria, and it was most likely made by hunter-gatherers who lived in the area. The environment at that time was much colder and bleaker then present-day, a remnant of Europe's last ice age.

The people who made this statue lived in a harsh ice-age environment where features of fatness and fertility would have been highly desirable.

The question is why were prehistoric humans stimulated by an exaggerated image such as this? The answer, according to neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran and others, lies in the workings of the human brain, in a neurological principle known as the "peak shift."

The people who made this statue lived in a harsh ice-age environment where features of fatness and fertility would have been highly desirable. In neurological terms, these features amounted to hyper-normal stimuli that activate neuron responses in the brain. So in Paleolithic people terms, the parts that mattered most had to do with successful reproduction - the breasts and pelvic girdle. Therefore, these parts were isolated and amplified by the artist's brain.

Egypt: Obsessive Order

By 5000 BC, the Egyptians had established a stable agriculture existence. They were the first settled humans to use images of the body extensively in their art. But the exaggerated, nomadic way of showing the body as a response to a harsh environment was long dead and gone.

Images of the human body were regular and repeated, and nothing about them was exaggerated.

Egyptian artisans lived and worked in groups, where originality was not highly prized. Images of the human body were regular and repeated, and nothing about them was exaggerated. Instead, the images were schematic and conceptual; schematic in the sense that they belonged to a larger plan, and conceptual in that the artist was more concerned with cataloging the parts of the body - one head, two arms, two legs, etc - then the actual appearance of the body. The Egyptians chose then to represent the human body from its clearest angle, and within a grid system that was applied to a plastered wall by dipping a length of string in red paint, stretching it tight, and then twanging it against the surface to be painted.

To the ancient Egyptians, their schematic and conceptual image of the body mapped within a grid system was a divine gift that would be spoiled by any deviation from the norm.

Ancient Greece: Naked Perfection

Ancient Greeks were preoccupied with philosophy and mathematics, but there was something in their culture that was the equivalent of Egypt's obsession with order and precision. The Greeks were fixated with the human body, and to them the perfect body was an athletic body. They believed their gods took human form, and in order to worship their gods properly, they filled their temples with life-size, life-like images of them.

The Greeks discovered they had to do interesting things with the human form, such as distorting it in lawful ways.

Greek sculptors first learned sculpting and quarrying techniques from the Egyptians. They initially created truly realistic depictions of the human body, like Kritian Boy (above), but within a generation they stopped this realism because it was too real -- for some reason they were dissatisfied with it. Though they didn't know it, just like the hunter-gatherers thousands of years ago they were looking for something more human than human. The Greeks discovered they had to do interesting things with the human form, such as distorting it in lawful ways in order to exaggerate the brain's aesthetic response to that body.

No comments:

Post a Comment